Ivan T. Sanderson — Chapter 8 — UFOs, Caves, Zoos, Fires, Floods

While conducting series on radio and television during those early years of the 1950s, Ivan also became a reporter for the North American Newspaper Alliance, a position which he held for more than twenty years. If something great or spectacular popped up around Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or New York, Ivan would race over and get a story. Such is the life of a reporter/free-lance writer.

On the evening of September 18th, 1952, Ivan left for Braxton County, West Virginia, on one of these assignments, perhaps the strangest of his career. He had gone to look into a report that a group of people had seen a “monster” by an alleged crashed spaceship in the woods out on a hill there. After a lengthy investigation Ivan concluded, on the basis of other sightings made on the same night, that several mysterious things came down out of the sky on the night of the Flatwoods incident, the objects in question having been seen flying over several populated areas and all going in the same direction before each “crashed” (all of them coming down within five to ten miles of each other) in West Virginia. Upon the arrival of reporters, the objects and the spaceman monster vanished, leaving a metallic stench and some crushed grass behind, along with a few bits of large reptile shells! This whole thing fascinated Ivan—he examines the incident and its subsequent, detailed investigation in a chapter of his book, Uninvited Visitors.

It was happenings such as these that influenced him into setting up the Ivan T. Sanderson Foundation, and later the Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained, a group which handled the study of such unexplained matters until the 1990s.

In addition to his work with the North American Newspaper Alliance, Ivan had become the vice-president in charge of public relations for the National Speleological Society (Society of cave explorers) from 1951 to 1954, during Charles E. Mohr’s presidency of that organization.

The Caves Beyond

Up until 1954, cave exploring in the United States had been only a weekend sport for small groups. In 1953, a number of “spelunkers” planned a huge assault on the Floyd Collins Crystal Cave in Kentucky, where the cave’s discoverer and tourist promoter, Floyd Collins, had been trapped by a boulder and died in 1925. Over 70 people would be involved in this subterranean expedition—64 directly in the cave—and the whole mess would undoubtedly attract throngs of people and reporters. Ivan drew up a plan whereby one reporter representing all of the wire services, one photographer from a national magazine, and one radio reporter representing a national network would be allowed into the cave to follow the expedition.

In February, 1954, wires were laid, spelunkers assembled, curiosity seekers gathered, and the whole operation performed successfully underground for a week. William B. Miller, NBC executive and reporter, got all the conversations he wanted for the NBC radio network; Robert Halmi, photographer for True magazine, took about 1500 black-and-white photographs and 500 color shots; and reporters from all manner of newspapers and wire services unrelentingly talked with expedition members via phone from above.

Joe Lawrence Jr. and Roger W. Brucker, the two expedition leaders, later wrote a book about the adventures they encountered underground with their group, entitled The Caves Beyond; The Story of the Floyd Collins Crystal Cave Expedition. (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1955).

The Animal Business

Ivan Sanderson's most daring pursuit during the 1950s was what generally could be called his “animal business.” Initially Ivan had "borrowed" animals from zoos in the New York metropolitan area for his TV appearances. In the summer of 1950 at a meeting of the National Speleological Society, he met 21-year-old Edgar O. ("Eddie") Schoenenberger, who by 1952 was his assistant in his animal business (and ultimately becoming essentially a partner, taking care of the business aspects by becoming president of a company Eddie called Animodels).

During 1950, Ivan was the Science and Research Director of Station WBAL-TV in Baltimore, on which he did a weekly show with his animals. Starting in 1952, however, he also began doing a weekly regular feature spot on the Garry Moore Show in New York, again with his animals, which continued until 1958. Then, in 1952, he also had a daily 15-minute show over WSTC, Stamford, Connecticut, on behalf of the Stamford Museum and Zoo. Clearly, Ivan had to find some better ways of distributing his animals around the country so as not to create difficulties with transporting them from station to station. For his shows in New York, Ivan had no alternative but to keep animals in his Manhattan apartment between visits with Garry Moore.

Once he was hauling around a baby hippopotamus. He obviously couldn’t get the poor creature in the elevator or up the five flights of stairs to the apartment, so he made arrangements with the landlord to keep it in the basement of the building for nearly a week. The baby hippo appeared on The Garry Moore Show on Wednesday, December 30, 1953.

Years later, a friend of mine—Doug Kirby, a member of the amusing bigfoot hunt mentioned elsewhere on this site—initially didn't believe the story but had the amazingly good fortune while attending a convention to strike up a conversation with a woman whom Ivan had persuaded during this time to drive each day from New Jersey across the George Washington Bridge, down the length of Manhattan to Ivan’s apartment building in Hell’s Kitchen, descend into the basement, and hose down the hippo!

When Ivan had first moved into the apartment, the rent was a mere 135 dollars a month. Several years later, the landlord circulated a small notice informing the tenants of the increased costs of upkeep and overhead in the building. He was only taking a poll to see how many tenants would object to a rent increase. Every tenant in the building stood dead set against the projected rent increase except Ivan. He had caused the landlord enough trouble, he thought, by keeping wild animals in his fifth floor apartment and in the building’s basement; therefore, a raise in the rent was more than justified.

The amazed landlord escorted Ivan into his office and said: “Mr. Sanderson, as long as you own that apartment... your rent shall always remain at 135 dollars a month.” He may have had second thoughts, later, though, considering that by the mid-1970s maintenance costs rose to the point where rent for other apartments in that same building ran well over 500 dollars a month. Today the rent in a comparable building would be at least 2,500 dollars a month.

The landlord must have been a very tolerant, patient fellow. Aside from the hippo-in-the-basement incidnet, he surely he must have heard tales of what Ivan's animals were up to in the building. TV pundit Al Morton describes the following:

FOUR SKUNKS, a female and her three young, escaped the vigilant eye of naturalist Ivan Sanderson, who was planning to exhibit the animals on CBS' "The World Is Yours." They wandered through the corridors of his large midtown apartment hotel. Searching for the roving skunks, Sanderson found that the night watchman, an old farm boy turned blase New Yorker had seen them all right, but hadn't thought it worth mentioning. He assumed they knew what they were doing. [Al Morton. "TV Roundup." Chester Times. (Pennsylvania) Thursday, 9 August 1951. p. 32.]

In October 1952 Ivan needed a photo of his Nicaraguan owl to promote a TV appearance, so he and Eddie Schoenenberger put it in a cage and brought it to the apartment of his long-time friend and associate, the photographer and herpetologist Roy Pinney, at 19 East 57th Street in Manhattan. As later reported by The New Yorker in its "The Talk of the Town" column:

The bird was in a cage and its owner opened the cage so that it could be posed, saying that the bird was quite tame. As he opened the cage the bird flew out toward Fifth Ave. where he lit on a flagpole outside of Stoufer's restaurant. The two men rushed out, dashed up to the 3rd floor of the restaurant and grabbed the bird. [Hellman, Geoffrey T. The Talk of the Town. "Diurnal Spree." The New Yorker. 25 October 1952. p. 26.]

Ivan Sanderson's Jungle Zoo along the Delaware

It was Ivan's assistant Eddie Schoenenberger who suggested that, instead of "renting" animals, they should purchase and house them, and gain some additional income by displaying them in a zoo. To accomplish this, Sanderson, in 1952 purchased a 250-year-old farmhouse and 25 acres of land a short ways from the ultimate location of the zoo between the communities of Columbia and Hainesburg. He immediately commenced refurbishing and expanding this, while also moving 200 of his rarest animals to a barn nearby so he could keep close watch on them and store them there between TV or live appearances. Then, in the Spring of 1954, he established the zoo itself, a permanent, summer, roadside facility along the Delaware River on King Cole Curve on Route 46, essentially in the town limits of Manunka Chunk, White Township, Warren County, New Jersey. It was on land leased from King Cole's, a BBQ restaurant (now defunct). Called "Ivan Sanderson’s Jungle Zoo" (and Laboratory), you couldn't miss it, since the name of the place was painted in large letters on a sign atop a 100-foot long wooden fence. (The zoo's sign painter, strangely enough, was Howard Menger, who often hung around Ivan talking about UFOs, and eventually became one of the famous "UFO contactees" of the 1950s.)

Ivan also developed and deployed winter traveling exhibits of rare and unusual animals for sports shows and department stores.

Ivan had a sort of private zoo back in Paramaribo, Surinam, on this third expedition, but that “zoo” was more of a temporary storage compound for collected animals that he was sending back to the museums and zoos. His zoo along the Delaware was stocked with a much wider range of animals than could be found in Surinam, ranging from the lowly “polecat” (skunk) to more exotic types of bats and other creatures. He despised the confinements of conventional zoos, and he wanted to create something that would eventually set an example for the rest of the world. Note too that this zoo was established nearly 20 years before Warner Brothers Pictures had the idea to build their ill-fated, 800-acre Jungle Habitat “safari theme park” facility in 1972 in West Milford, also in the same area of northern New Jersey .

Shortly after the zoo was constructed, Ivan found that it was difficult for him to commute between his home, his zoo and his apartment in New York City (#516 in the Whitby building on 325 West 45th Street, which he maintained until his death). His rarest species housed in a barn next to his home required special close supervision, and fighting his way through traffic every day to instruct his assistants on care and feeding did not suit him at all. Most residents of the area were simple-hearted folk of Holland Dutch (German) extraction, and so when the imposing figure of Ivan T. Sanderson descended upon their complacent countryside, bringing his 200 rare, squeaking, snorting, and growling animals with him, one wonders what the local naivete thought of their famous new neighbor and his barn emanating a Tarzan movie soundtrack.

Transporting these animals several times a week to the various stations was not without its misadventures either. Ivan moved his animals with the aid of a large multi-seat station wagon of the kind used for transferring VIP passengers to and from planes at airports. One day Ivan confronted his neighbor, Allen V. Noe, with a problem: Monkey urine had accumulated in the well holding the spare tire. Noe got out his electric drill—and began to bore a hole through the bottom of the well, so that the 'problem' could drain out.

Suddenly Noe stopped drilling.

“Ivan,” he asked, “where is the gas tank on this car?” An examination revealed that the gas tank was located directly beneath the spare tire well. He was close to emptying the contents into the gasoline and essentially wrecking the car. Noe then got hold of a screwdriver, fished around and discovered a small screw at one end of the well. Upon unloosening it, the problem soon drained away.

“Thanks for not drilling a hole in my gas tank,” said Ivan. “Things will certainly smell a little fresher in there from now on!”

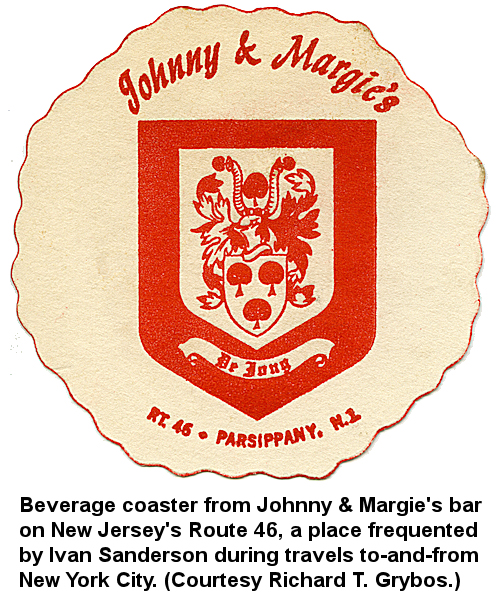

A Traveler's Oasis: Johnny & Margie's

When traveling back-and-forth between his New Jersey residence and his apartment and/or TV shows in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, Ivan and his cohorts would get a hankering for some alcoholic libations around each trip's halfway mark. They would inevitably stop for liquid refreshment at Johnny & Margie's bar, owned by Johnny DeJong and his wife, on Route 46 in Parsippany, New Jersey. Former SITU resident staff member Richard T. Grybos was kind enough to rummage through his belongings and found a cocktail coaster he had pocketed during one visit to the bar—I couldn't resist scanning it and posting it on this page.

Saved by the Mob

This is most likely a tall tale about Ivan (as told to me by his friend, Adolph Heuer, Jr.) but I can't resist presenting it here for your amusement...

One day in November 1957, while driving south of the Catskill Mountains in search for some specimens, Ivan Sanderson came across a large black limousine, apparently both lost and broken down by the side of the road. Realizing that there was little-to-no traffic, Ivan stopped his car and offered to help. He ended up towing the car with great difficulty for many miles out of his way, finally arriving at a location at Apalachin, New York, where the V.I.P. in the limo was to meet up with many of his like-minded colleagues for a very important meeting.

The mysterious V.I.P. got out of the limo, shook Ivan's hand and intimated that he had done him a great service.

He handed Ivan a card with a phone number and a name on it.

"If you ever need help—anything at all—call this number, mention this name, and just ask," he said.

Some time later, Ivan had transferred a number of animals from his zoo to a warehouse in New York City that he used as a temporary holding area for them before they were shown on television. New York City laws prevent one from having such exotic animals housed anywhere outside of a zoo, so Ivan found himself continually bribing the local police.

In this particular instance, when an officer of the law confronted him at the warehouse, Ivan didn't have much cash on him. Ivan asked if the officer would accept a check. The cop looked askance at him and growled that he had until 5 p.m. to get his animals out of there, or else they would all be seized. The cop stormed out.

Ivan, shaken by the encounter, at first didn't know what to do. But then he remembered the card in his wallet, given to him by that charming Italian fellow in the limousine.

Finding a phone, Ivan took out the card, dialed the number, mentioned the name, recounted the story of how he helped out the gentleman in the past, and explained that he was at a warehouse on so-and-so street and such-and-such avenue, and he needed to get his animals out of there by 5 p.m.

There was a moment of silence. A voice at the other end of the line uttered a single word: "Done!" then hung up.

Ivan waited, not knowing what would happen next.

After less than an hour, he heard a rumbling noise outside. There was a knock at the door. A man was standing there. He spoke: "You Ivan Sanderson? We're here for the animals. Where do you want us to take them in Jersey?"

Ivan looked out to see a couple of huge trucks pulling up to the loading docks. Ivan and a team of workmen hurriedly got all of the animals, feed, and equipment on board the vehicles and they drove off.

At 5 p.m. the police raided the warehouse, only to find that it was now empty—in fact, practically stripped to the floor. No animals, no Ivan Sanderson.

The Rowing Octopus Yarn

Ivan Sanderson was pretty good at training animals, but probably the strangest rumor about what he did in this respect involved teaching an octopus how to row a boat. Yes, you read that correctly. I first heard of this in the 1970s from his former literary agent, Oliver Swan. (Swan, who began his career working with the agent Paul Revere Reynolds, was a bit of an odd fellow. In the short time I knew him before his death, Swan repeatedly voiced his dislike of authors using the word "even," as in the sentence, "He didn't like desserts—he didn't even like ice cream.")

According to Ivan's former assistant, Edgar O. Schoenenberger, the wild tale of the octopus that could row a boat came from Roger Price, who published the syndicated column "Droodles" in the 1950s and 60s. Droodles are nonsense cartoons that first appeared in Price's 1953 book, Droodles. The trademarked name "Droodle" is a nonsense word combining both "doodle" and "riddle." Frank Zappa used one of Price's original Droodles to illustrate the cover art for his 1982 album, Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch.

In any case, Price's "Droodles" column that appeared in U.S. newspapers on August 31 and September 1, 1955 showed a drawing sent in by Mrs. Claude L. Watson of Winston Salem, North Carolina, entitled, "Octopus Scratching Its Back." This was the starting point for Price's fanciful imagination. To the drawing and initial description he added the following hilarious text:

...Ivan Sanderson, the animal expert, once had a pet octopus he kept in a tank in his apartment that was really smart. Ivan taught the octopus to row a boat, eat with knives and forks (four each), wear a sailor hat and play the piano, a clarinet and ping poing (all at the same time). And sometimes the octopus would hold a stick in its mouth and let Ivan use it for a mop. It could also count up to 8. In fact, the octopus was so intelligent Ivan used to call it his "Quiz Squid." [Roger Price. "Droodles. " El Paso Herald-Post (Texas). 1 September 1955. p. 3]

Today, of course, we know that the octopus is quite an intelligent animal and can even engage in "play" behavior. If Price had just stuck to the "rowing the boat" claim, more people would have believed it.

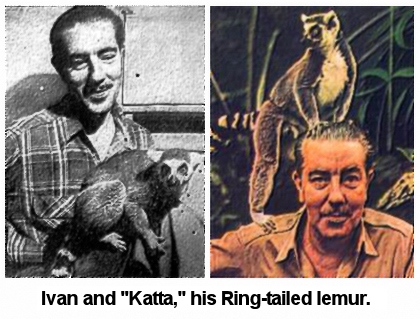

Disasters and More Disasters

Advance planning for the care of his animals was of no help to Ivan Sanderson, for certain unforeseen disasters took place. His unique animal collection was destroyed in a fire on the night of Wednesday, February 2, 1955, while Ivan was in New York doing a TV program. All of the little creatures perished but five, an African sheep and four animals with Ivan in New York, including his male Ring-tailed lemur from southern Madagascar named “Katta,” who was Ivan’s pet and loyal assistant, trained in insect collecting. He kept Katta for over 12 years thereafter—and then it belonged to Edgar Schoenenberger for 26 years after that.

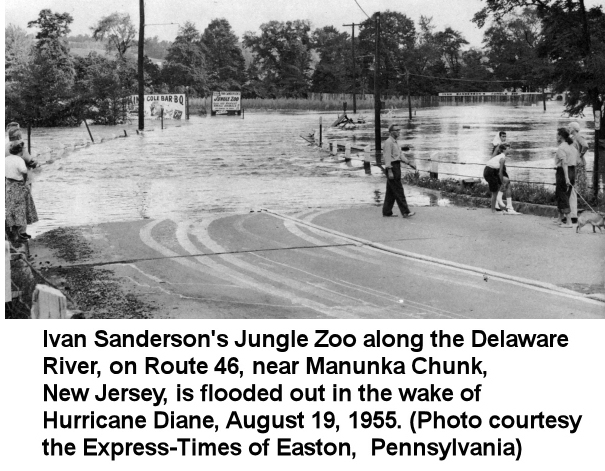

Another big disaster struck when Ivan's Sanderson's Jungle Zoo itself, containing all of the larger animals, was flooded by the Delaware River on August 19, 1955. The area had been hit by two hurricanes in succession: Hurricane Connie, starting August 11, and the infamous Hurricane Diane, starting August 18, which resulted in the Delaware's greatest flood in recorded history, drowning at least 72 people.

Another big disaster struck when Ivan's Sanderson's Jungle Zoo itself, containing all of the larger animals, was flooded by the Delaware River on August 19, 1955. The area had been hit by two hurricanes in succession: Hurricane Connie, starting August 11, and the infamous Hurricane Diane, starting August 18, which resulted in the Delaware's greatest flood in recorded history, drowning at least 72 people.

Most of the zoo's living exhibits were moved out in time and transported elsewhere before the flood peaked, thanks to the frantic efforts of Ivan and two of his assistants, Edgar Schoenenberger of Huntington, New York (who was also president of Animodels, Inc. which exhibited Ivan's animals at special events), and Patricia Vanatta (Eddie and Patricia would eventually marry and today live in Ivan's former home). Jocko, a 37-year-old, 7-foot long, 122-pound Cuban crocodile—or "Jock the Croc" as newspapers would refer to him—was not going to be so easy to handle. Jocko originally belonged to a woman whose father had purchased him in Florida and brought him back to their home in Brooklyn, New York. Jocko basically lived in the family's bathtub, periodically transferred to the backyard lawn during times when family members needed to take a bath. After Jocko grew to be an unmanageable size, the family contacted Ivan and the Cuban crocodile was moved from Brooklyn to his zoo.

Now, as the Delaware River's waters continued to rise, peaking 43 feet above normal, Schoenberger, then age 25, swam to Jocko's cage with a pair of wire cutters and snipped a hole in the fencing, allowing the creature to escape.

When the waters receded, Jocko’s body was nowhere to be found. After a fruitless search for several weeks, it was assumed that the crocodile had drowned.

Cuban Crocodiles, however, are strong swimmers and the favor freshwater habitats such as swamps, marshes, and rivers (even the Delaware). Reports of the "potential man-eater” cropped up in all sorts of places, but none of these sightings could be confirmed. Moreover, the temperature of the Delaware River in the fall and winter was not exactly conducive to the survival of crocodiles, Cuban or otherwise. Still, Ivan warned everyone that if they saw Jocko, they should not try shooting at him, since, if wounded, the crocodile would be extremely dangerous.

Cuban Crocodiles, however, are strong swimmers and the favor freshwater habitats such as swamps, marshes, and rivers (even the Delaware). Reports of the "potential man-eater” cropped up in all sorts of places, but none of these sightings could be confirmed. Moreover, the temperature of the Delaware River in the fall and winter was not exactly conducive to the survival of crocodiles, Cuban or otherwise. Still, Ivan warned everyone that if they saw Jocko, they should not try shooting at him, since, if wounded, the crocodile would be extremely dangerous.

Then, in early October 1955, Betty Conrad of DePue's Ferry found strange impressions and tracks in the sand at the river's edge five miles below the flood-destroyed zoo. She soon sighted Jocko, who had been lured across the river by the warm water discharged by a electrical plant belonging to the Pennsylvania Power and Light Company. [Frank Dale. Delaware Diary: Episodes in the Life of a River. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996.]

Paul Conrad, 45, of Depue's Ferry Road and Eddie Schoenenberger rushed to the scene, spotting the creature on the Pennsylvania bank of the river on the afternoon of October 4. Schoenenberger used a rope to lasso Jocko's neck. Jocko's 45-day vacation had ended. ["Lasso Ends Crocodile's N.J. Jaunt." Associated Press, 5 October 1955.]

"Jackco (sic) was trussed up quickly and returned to the zoo." ["Crocodile Hunt Ends." The New York Times., 5 October 1955.]

The great Delaware Flood of August 19, 1955, helped to usher Ivan out of the zoo business. He continued to import animals, though, until June 1958 when Garry Moore's daytime show went off the air.

Ivan Sanderson continued to make personal appearances, such as his attendance as a guest for the formal opening ceremonies of the 500-acre Birch Hill Game Park near Brewster, New York, on September 1, 1956. [The Billboard, 1 September 1956.]

The Billboard [May 13, 1957, p. 77] states that Eddie Schoenenberger was president of Animodels, Inc., and that, "for the second successive season, May 19–September 15, Ivan Sanderson's Animodels exhibit will be a Boardwalk feature at Asbury Park, New Jersey." The show was part of the Americana exhibits in the Casino Building. Like most of Sanderson's traveling exhibits, the show specialized in small, rare animals from various parts of the world.

Ivan's Post-Animal World

With the demise of the daytime Garry Moore show in 1958, Ivan began to rid himself of his animal friends (except for his beloved Ring-tailed lemur, Katta) and went back to writing books and articles, also taking time out for a long excursion through North America to write The Continent We Live On. He even appeared personally on a few TV game shows where he would compete with scientists and teachers for cash.

Around this time (1960-1962) Ivan's mother died. He said that his health "broke down for a while" at this time. (Actually, he had various illnesses over the years, as did his wife, Alma, who nearly died twice before she contracted the cancer that ultimately led to her death.)

All was then well with Ivan for the next several years, until he established the Ivan T. Sanderson Foundation and began to devote the greater part of his energies to unexplained phenomena. It was only then that most of the world (and some of his fellow scientists) turned against him and his views, as we shall see later.

Home — Next: Chapter 9: Sidetrip: Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett — Top of Page